That Africa is a diverse continent has been the hallmark of many descriptions of the continent. This diversity can be seen in many aspects of the continent, but in few does it show more than in the languages spoken by its people, estimated to be up to 2000. From the clicks of the Khoisan to the lyrics of the Arabs, Africa is a vast and beautiful symphony of sounds and tongues. In these sounds is to be found the identity and history of entire peoples, some of whom are very many, like the Hausa of Nigeria.

But, like all good things traditionally African, many of these languages now seem threatened by the growth of foreign, and utilitarian, English. A language that knows nothing of the subtleties and nuances that have made the people of Africa who they are now. A language that can only scratch the surface of African depth. A language that is only suitable for enjoying the benefits of the modern world. So there is a flurry of activity, driven by the apprehension that these languages may one day disappear, to find a means of preserving them for posterity.

One of the measures chosen is to commit these languages to paper in the form of books. Ngugi wa Thiong’o, a foremost Kenyan intellectual, now writes his books in his native Kikuyu, from which they are then translated to English and other languages. In itself, this is a most noble undertaking, and one from which I do not endeavor, and cannot even hope, to dissuade him. Who knows, it may yet make of an African language on the decline a literary tongue. But — let’s be realistic here — is this the way? Will this keep our languages from disappearing?

The answer is simple. No. First, nobody, except people in Church on Sunday, reads works of literature written in a local language. This is the case in Kenya, and this is the case in multiple regions of Africa. Furthermore, even this practice is on the decline. More Masses in Catholic parishes across Kenya are now being said in English or Kiswahili. And as if that was not enough, Africa now has an entire generation of young people, many of whom either disdain or have never spoken their mother tongue. Is it their fault? I don’t think so. By writing in Kikuyu, Ngugi’s original works are now limited to a tiny portion of a tiny tribe (this is not a disparagement). And we all know translations suck.

So writing won’t help. If anything, writing would actually limit these languages. One great feature of many African languages is that they have developed around a rich tradition of oral literature. This is in contrast to the great literary languages of the world, which developed around writing. Much of modern English, for instance, is reckoned to Shakespeare, who was primarily a writer, not a speaker. From the Chaucer to Rowling, English has developed as a literary language. It is therefore no surprise that many of the great works of literature can be found in it. The same is true of the Romance languages, which are offshoots of Latin, a written language much like any other. Chinese, Japanese. These are all written, and have developed alongside writing or after encountering writing. And that is not a bad thing.

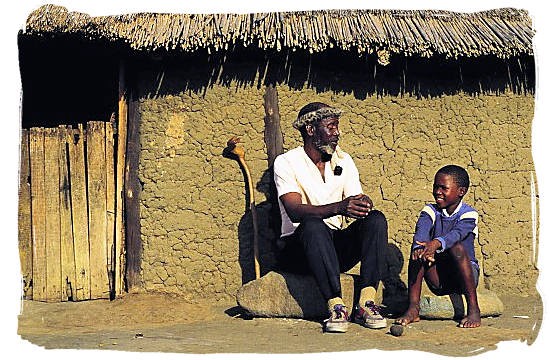

But African languages developed around oral tradition. It was the abandonment of this phenomenon that led to the decline of these languages. The young men and women who never use their native tongues have never been given, in the form of epic tales told orally, any reason to use them. They have not savoured the richness of their dialect, because no one has ever given them reason to. The tales I used to hear from my sister when I was a little child are no longer told.

To write in a native language, as I have said, is a good thing. But it cannot save a language from extinction, unless the language finds a potent patron like the one Latin found in the Catholic Church and medieval scholars. It is only a return to the tradition of oral literature that will save our languages. If the epic tales of pre-Colonial Africa, and those of after, could be told again in our languages, then there could be some hope.

Now, you may ask, how is that to be done? The answer already exists. Audiobooks. Pure audiobooks recorded primarily in that format. Without a written book behind them. Get the old people who still remember the tales of old to tell them. Record these and distribute them. Our languages are conversational. They are not to be confined to characters on a piece of paper. If the means by which they are born and nourished, which is oral literature, is not used to keep them alive, I don’t know what will.

But it has to be borne in mind that even these attempts won’t guarantee stability to these languages. Like all languages, ours will change and morph and, two hundred years from now, will be greatly at variance with the tongues we know now. That is normal, but it won’t happen, of course, if we let them die off completely.

Feature image: South Africa Tours and Travel.

Sign up to receive new articles as soon as they drop.